Brant Cooper and Patrick Vlaskovits had three goals in mind when they set out to publish The Lean Entrepreneur: How to Create Products, Innovate with New Ventures, and Disrupt Markets.

The first was to describe why our economy is primed for a new wave of entrepreneurship using new methods of disruptive innovation. The second was to provide real-world examples of how entrepreneurs are creating new markets and disrupting others. The third was to show you how anyone interested in starting a new business or launching a new idea can get started creating value.

They accomplished all three quite well, but I found the most valuable part of the book to be the sixth chapter, which outlines several ways to conduct the kind of scrappy experiments you must run to determine whether an idea has any real chance of becoming something innovative and commercially viable.

Ideas Are Not Innovations

I'm constantly amazed at how often I see people confusing an idea with an innovation. The difference becomes quite clear once you've run a few experiments with some element of the idea.

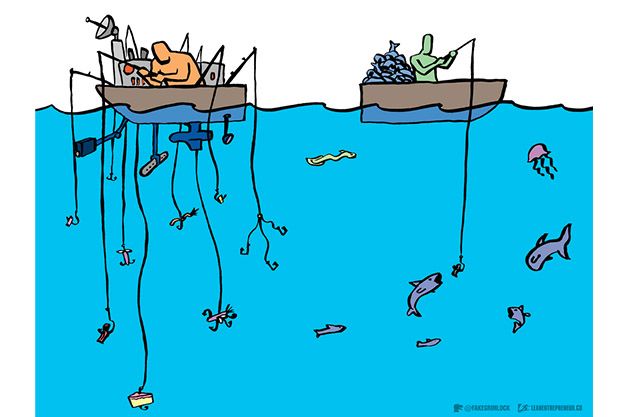

But there's the rub: Most people struggle to understand what they must do when it comes to testing an idea. In fact, they struggle with the idea of trying to fail early in order to succeed later. Instead, they assume their idea is a good one (it usually isn't), craft a business plan (which holds little relevance in today's disruptive environment), run some numbers (mostly fantasy resting on a leap of faith assumption) and seek investment capital to run with it. They confuse asking potential customers what they may like about the idea, or what they might do in the future, with what they will actually do.

Months down the road, when that great idea fails miserably, they scratch their head and wonder why it didn't work.

The Lean Entrepreneur, which takes its cues from the work of Eric Ries (The Lean Startup) and Steven Blank (The Four Steps to the Epiphany) and synthesizes it into a tactical playbook, goes a long way toward preventing all that pain and waste.

Testing, Testing, 1, 2, 3

Here are three great ways to quickly test your idea before you sink any real resources into it:

1. Landing Page. The authors suggest that "you put up a basic one-page website comprised of your messaging and a call to action, drive traffic to the page, and measure clicks on the call to action." This allows you to test three crucial variables: your customer acquisition method; the quality of your messaging, positioning and design; and, perhaps most importantly, how attractive your value proposition really is.

Example: AppFog is a platform-as-a-service (PaaS) that allows Web and mobile app developers to deploy, scale and run their apps in the cloud as easily as installing an iPhone app. It started with a landing page test that generated 800 email addresses in one day. But the founder, Lucas Carlson, wanted to weed out the sayers from the doers, so he created a burdensome survey. The overwhelming 50 percent response was enough to propel him to the next stage of development.

2. Concierge Test. This is testing by doing. Like the authors, I'm constantly bombarded with online multi-sided marketplace ideas, aka "grand plans to build an online platform that brings together two or more parties who aren't readily accessible to each other."

In a Concierge Test, you manually perform tasks related to your service, tasks that will eventually be automated, and actually derive revenue from them. If you think about it, this is the Holy Grail of tests … getting people to part with their money is, after all, the ultimate goal of a business.

Example: TakeLessons began as Click for Lessons, a lead-generation site for musicians wishing to teach in order to make money while they waited for their big break. Co-founders Steve Cox and Chris Waldron recruited 30 instructors by hand, got them to sign agreements, and then matched them by hand to actual students. To find students, the pair hacked together a call center and published an 800 number, and for half a day took calls from possible students and for the other half of the day recruited teachers.

3. Wizard of Oz Test. Like the Concierge test, the Wizard of Oz test requires virtually no actual product development. As the authors write: "It could also be called the Hamster Power Generator test, similar to the cartoons in which you discover hamsters on exercise wheels are powering the car engine. Basically, you provide a front end for your product where someone can buy, yet you fulfill the product’s purpose manually."

Example: If you visit Zappos, you'll see the early company history in the lobby. Nick Swinmurn reserved the domain name Shoesite, walked down to the local shoe store, took pictures of their shoes, and posted them on the site. It wasn't long before he was generating thousands of dollars in orders, without building any kind of inventory system. The point was not to make money, but to test market risk of the central idea (selling shoes on the Internet).

I strongly recommend that anyone with a business idea pick up and devour The Lean Entrepreneur. Focus on "Chapter 6: Viability Experiments" and "Chapter 3: Wading in the Value Stream." Run the experiments that are applicable to your idea. Come up with the behaviors that will signal where potential customers are on the value stream continuum, from becoming aware of your idea, through to becoming passionate about it.

As Thomas Edison once said, “The real measure of success is the number of experiments that can be crowded into 24 hours.”

And 24 hours is quickly becoming the average lifetime of an idea.

Read more articles on leadership.

Photos from top: Courtesy Wiley, Courtesy The Lean Entrepreneur by Brant Cooper and Patrick Vlaskovits with illustrations by Fake Grimlock, Thinkstock